A new study suggests that meteorites may be a food source for living things, more specifically a microorganism called Metallosphaera sedula, a metal-eating species.

Metallosphaera sedula is a species of bacterial-like microbes originally isolated from a volcanic field in Italy. The first part of the name can roughly be translated as “metal mobilizing sphere”, while “sedulus” means busy. This describes the efficiency of these organisms in mobilizing metals, including those found in asteroids.

According to research led by University of Vienna astrobiologist Tetyana Milojevic, these microbes derive their energy from inorganic substances through oxidation, and can collect energy sources faster from extraterrestrial rocks than from simple ancient terrestrial minerals. Milojevic explains that the study was conducted to find “microbial fingerprints” left in meteorites. “This should be useful for tracking life-seeking biosignatures in other parts of the universe,” he concludes.

This kind of research, according to the astrobiologist, can provide her colleagues with “little tips” on what they can look for in their search for alien life. “If there was ever life on another planet, similar microbial fingerprints may still be preserved in the geological record,” he said.

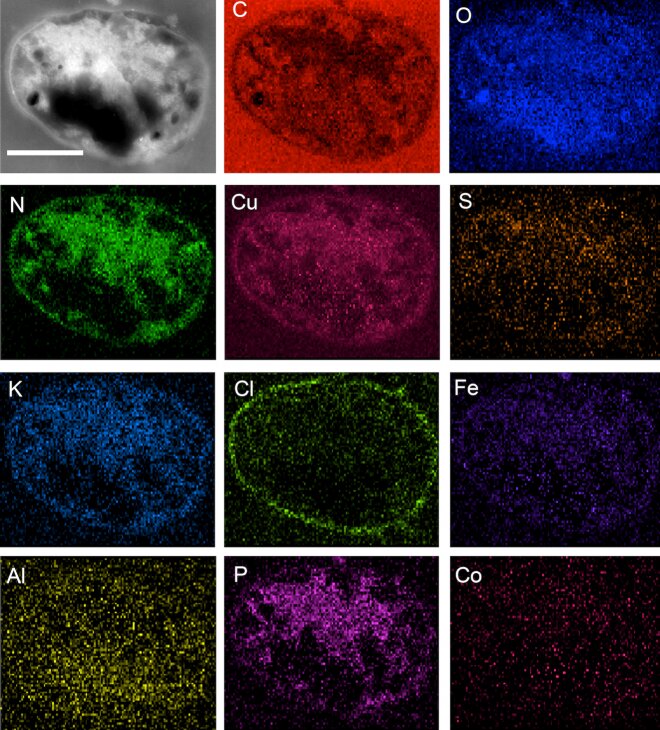

The team examined how Metallosphaera sedula interacts with NWA 1172, a rocky meteorite found in northwest Africa that contains about 30 different metals. Using various spectroscopy techniques and an electron microscope, the researchers documented the signatures left by the organism. Thus, they found that M. sedula is able to consume extraterrestrial material much faster than it does with terrestrial minerals, resulting in healthier cells.

While terrestrial minerals provide only a few nutrients for the microorganism, “NWA 1172 iron is used as an energy source to meet M. sedula’s bioenergetic needs as microbes breathe due to iron oxidation,” Milojevic explained. The wide range of metals in NWA 1172 can also be used for other metabolic processes, such as accelerating vital chemical reactions within cells. And because the meteorite is so porous, it can promote M. sedula’s improved growth rate.

That means iron meteorites could have brought more metal elements and phosphorus to Earth, making life’s evolution easier, according to Milojevic. In addition, research may also support the panspermia hypothesis, an idea that cannot yet be substantiated, but it is not ruled out either, as scientists have not yet completely unraveled the origin of life on our planet. And Milojevic is interested in exploring this possibility: To do so, her team plans to “test the survival of M. sedula under simulated and real environmental conditions from outer space,” the astrobiologist said. The plan, however, will have to find the funding needed to send the microorganisms into space.