At the end of 2019, it is time to remember what were the biggest science fiascos. But first of all, let us point out that learning also comes out of every mistake – and in science, making mistakes is often part of the process towards progress.

“There are many hypotheses in science that are wrong. This is perfectly acceptable; they are the opening to finding the right ones.” – Carl Sagan

So the failures listed in this story are worth remembering, but not mocking – everyone involved in these flops has certainly learned a lot from their flaws towards success in future endeavors.

“I have not failed a thousand times. I have successfully found a thousand paths that did not work” – Thomas Edison

Landing on the moon is hard – and Israel felt it “in the skin”

In February, Israeli startup SpaceIL became the first privately owned company to launch a ship to the moon. The Beresheet landing was scheduled to take place in April, but as the world watched the live broadcast of mission control and its telemetry data, in the final minutes of the descent the controllers lost contact with the ship – and everything indicated a tragedy.

Shortly thereafter, the company revealed that the ship’s engine had failed, and confirmed that Beresheet had, unfortunately, just crashed into the lunar ground. The crash happened when the ship was only 14 km away from the moon’s surface, and it was impossible to reduce its speed by 500 km/h to prevent collision.

In subsequent days, SpaceIL announced new funding to build a Beresheet 2.0 and, with it, try to reach its goal of landing on the moon – but in June the company backed down, at least with regard to a new lunar landing. The new Beresheet would then target another body of the Solar System (not yet released).

But the #fails in this story are not just because of the “crashed” spacecraft on the moon and giving up trying to make a new lunar landing: Beresheet shipped with it a number of scientific charges that even NASA would use, including a retroreflector device and an artifact which would measure the lunar magnetic field, as well as a disc with a gigantic collection of human information and knowledge that would initiate the creation of a “lunar library”. This archive also had 30 million documents that would serve as a primer on humanity, and the company’s idea would be to feed this space library with more information on future missions – which, it seems, will no longer happen.

And it doesn’t stop there: months later, in August, it became public knowledge for the first time that the Israeli ship was also carrying another cargo, which contained microscopic animals. Then, with the collision, thousands of tardigrades may have been released on the lunar surface. Highly resilient, they are theoretically capable of surviving in the harsh conditions of our natural satellite, but it is not known to this day whether the shell that protected them remains intact, or whether the so-called water bears were actually dumped on the moon.

Landing on the moon is difficult – and India understood the drama of the Israelis

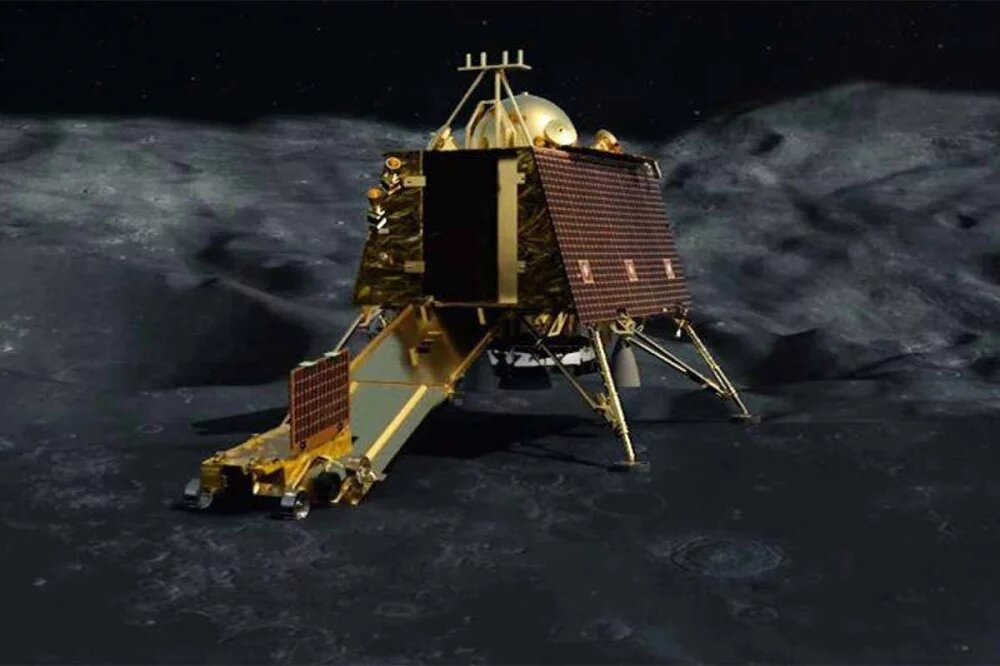

Launched in July, the Chandrayaan-2 mission would take India a second time to the surface of our natural satellite, carrying an orbital probe, a landing module and a rover – which would make it the fourth to land a ship on the moon, following in the footsteps of Russia, the United States and China. However, in the so-called “15 minutes of terror” during the descent of the Vikram module, mission controllers lost contact with the spacecraft, and it took a long time for the ISRO space agency to confirm the collision – which only happened in November when Finally, they revealed a problem with the braking thrusters when the ship was only 2.1 km away from the ground.

But the mission cannot be classified as a complete failure because of this: only the Vikram landing module and the Pragyan rover could not accomplish their mission, as the Chandrayaan-2 orbital module has been successfully positioned and continues to send data and provide learning, since then. That is why ISRO has not given up on trying to explore the moon: India announced in October a partnership with Japan to fetch water from the moon in 2023, and the following month revealed that by 2020 it will launch Chandrayaan-3 to continue what Chandrayaan-2 could not do.

Mars One and the “Schrödinger Bankruptcy”

Died but well? Bankrupt and not bankrupt at the same time, depends on the point of view? We’re talking about startup Mars One, which has been causing controversy and even being called a scam since its inception in 2012.

In 2013, the Dutch startup announced that it would start looking for candidates to start a human colony on Mars by the year 2023, with the ambitious goal of initially bringing up to 20 people there. The company has received numerous sponsorships over the years, but has quickly begun to be criticized by the international scientific community for the fact that current technologies still do not guarantee the long-term survival of humans on the Red Planet – let’s remember that NASA itself has plans to send their first astronauts there only in the 2030s, in an optimistic projection.

Now let’s jump to 2019: In February, the company filed for bankruptcy, which was discovered by a netizen who threw the *** on the fan through Reddit. Mars One was comprised of the nonprofit Mars One Foundation and the capital arm Mars One Venture – the latter bankrupt at the beginning of the year when it was estimated to be worth $100 million, and in July From the previous year, the company snapped up a $14 million investment with a private company.

But “out of the blue” that same month, the company said it found a mysterious investor who would represent its financial salvation, paying about $1.1 million it owed to its creditors. The investor would also inject more money into the company so that it would put its project back on track, turning Martian colonization into a kind of reality show.

Since then, the company has even made some random postings about Mars on its official blog, but nothing more has been said about its financial status, much less about the progress (or not) of its project. On Twitter, Mars One hasn’t posted anything since March.

NASA Commercial Crew Program Delayed with Boeing and SpaceX #fails

The Commercial Crew Program is NASA’s program that has chosen Boeing and SpaceX to develop manned spacecraft with the goal of independence from the United States from Russia regarding the sending of US astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS). Since 2011, the country has been relying on Russian Soyuz rockets and ships for this transport, and the US agency’s commercial program has given good money to the companies of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos to break this dependence on former space exploration rivals.

But many unforeseen events (and even incidents) marked the program, causing the start of testing with the two companies’ ships to be delayed. In fact, if you consider NASA’s initial plans, they are already more than two years late, which would finally be eliminated in 2019… They would be, because this year was marked by another set of setbacks.

In February, the space agency explained that the first tests scheduled for 2017 were postponed with a new schedule for 2019, which could not be followed either – the prediction was that SpaceX would test the Crew Dragon at a launch in February, while Boeing would do the same with Starliner in March. The new schedule then placed SpaceX’s first unmanned test for March, with the same being done by Boeing in April. Musk’s first manned flight would take place in July, with Boeing’s manned flight rolling in August.

When did all this happen? Well, SpaceX managed to make a first unmanned flight with Crew Dragon in March, but so far it has not been able to continue with the other plans because, in May, the ship exploded during a new test with its engines, which delayed more once, the rest of the schedule. In late September, NASA criticized SpaceX for all of this, and Elon Musk promised to approve Crew Dragon to fly “within three to four months” – which hasn’t happened yet.

Boeing, on the other hand, could only get Starliner to fly for the first time now in late December, but a problem during the flight prevented it from reaching the ISS, returning to Earth early. This flight was unmanned.

With all this, NASA remains dependent on Russia to send its astronauts to the ISS, and in order not to risk spending how long without any Americans occupying the orbital station, NASA may have to pay more seats to the Russians by 2020.

More “roll” with SpaceX – this time with the Starship rocket

Another issue SpaceX has been dealing with is related to its powerful new Starship rocket, which has been promised and reported for years, too. It is with him that the company intends to carry cargo and people into space, both on the moon and on Mars – as soon as possible.

A prototype Starship “jumped” for the first time in April, and it all worked out then. In early July, the company announced that the final version of the rocket would fly for the first time in 2021, capable of carrying up to 20 tons of cargo to Earth’s geostationary orbit, over 100 tons to low orbit, and up to 100 people to the moon or Mars.

But this schedule may need to be revised. Still in July, the rocket prototype caught fire during tests on its engine, but by the end of the same month, a new prototype was able to reach an even higher altitude in a new “jump” test. Everything went relatively well throughout the year, until in November another rocket prototype exploded during further testing – before that, Musk even said Starship would start flying at low altitudes as early as 2019, with a version most powerful reaching Earth’s orbit by March 2020.

And yes, more “roll” with SpaceX – now involving Starlink satellites

2019 was not an easy year for Elon Musk, whether it was starring Twitter scandals and “drunkenness” or its space endeavors. In addition to the “rollers” mentioned above involving the Crew Dragon spacecraft and the Starship rocket, their SpaceX has also been (and continues) involved in a problem with the scientific community: their Starlink satellites are already disrupting astronomical observations made from terrestrial telescopes. Fundamental to SpaceX’s revenue, the Starlink project aims to create a constellation of satellites orbiting the Earth to provide high-speed internet across the globe. In May, the first 60 units were launched, with another 60 lot being launched in November. The project aims to launch between 30 and 42 thousand units, starting its operations, although in a few regions of the United States, as early as 2020.

Astronomers have already worried that satellites may reflect sunlight and have disrupted their observations since their first launch in May – and Musk, via Twitter, said it would not. However, by that time the first 60 units have caused some trouble, with the next 60 units actually disrupting some observations – with diverse images being released by scientists proving their allegations.

After the “breath”, SpaceX went public in December saying it is not meant to be an enemy of astronomy, so it was planning to coat upcoming satellites to be launched with a kind of dark ink that would reduce reflectivity and thus, would solve the problem. However, many tests have yet to be done before this idea is effective, and until then the problem continues to affect the work of astronomers who rely on ground-based telescopes to work.